Standing in the vineyards of current owner, and third generation, Marco Mantengoli, I could feel the polarizing weather of the morning-side exposure in south-east Montalcino. When the heavy cold wind would stop for a moment, the intense sun would burn your skin. While the vines haven’t even begun to flower, I could sense a perfect combination between ripening the fruit and retaining acidity and aromatics.

Marco inherited 4ha of vineyard land from his father, Vasco, and has since expanded the property to 12ha. Not an easy feat considering land in Montalcino DOCG can cost on average 600,000 euro per ha. The original 4ha was in an average state; Mostly grains, the vineyard had diseases and the vines were in need of re-planting. “We are a farmer looking for the best result from their work, not money.” exclaims Marco.

Montalcino’s history is unlike the rest of Tuscany. A few very rich landlords owned large extensions of land with sharecroppers residing. Those families individually farmed the lands by use of the landlord’s equipment. 50% of the produce had to be given to the landlords, which after WWII was abolished. Montalcino, on the other hand, were rebels. They didn’t want to be part of the Florentines and therefore settled here with independent small farms with no landlords. This is the ‘Montalcino Spirit’.

Marco’s vineyards are all located around his winery and home. The youngest part of the vineyard, closest to his home, was just replanted in 2014 and will be used for his IGT wine. Vines here haven’t dug deep enough into the soil and express the character of the soil into the wine. The oldest vines, 20 years and over, will go into his Brunello while the medium aged vines for Rosso di Montalcino. In between the vines grow fava beans which incorporate nitrogen to the soil, a type of natural fertilisation. “To search for natural equalibrium and to put the best situation for the plant.” explains Marco.

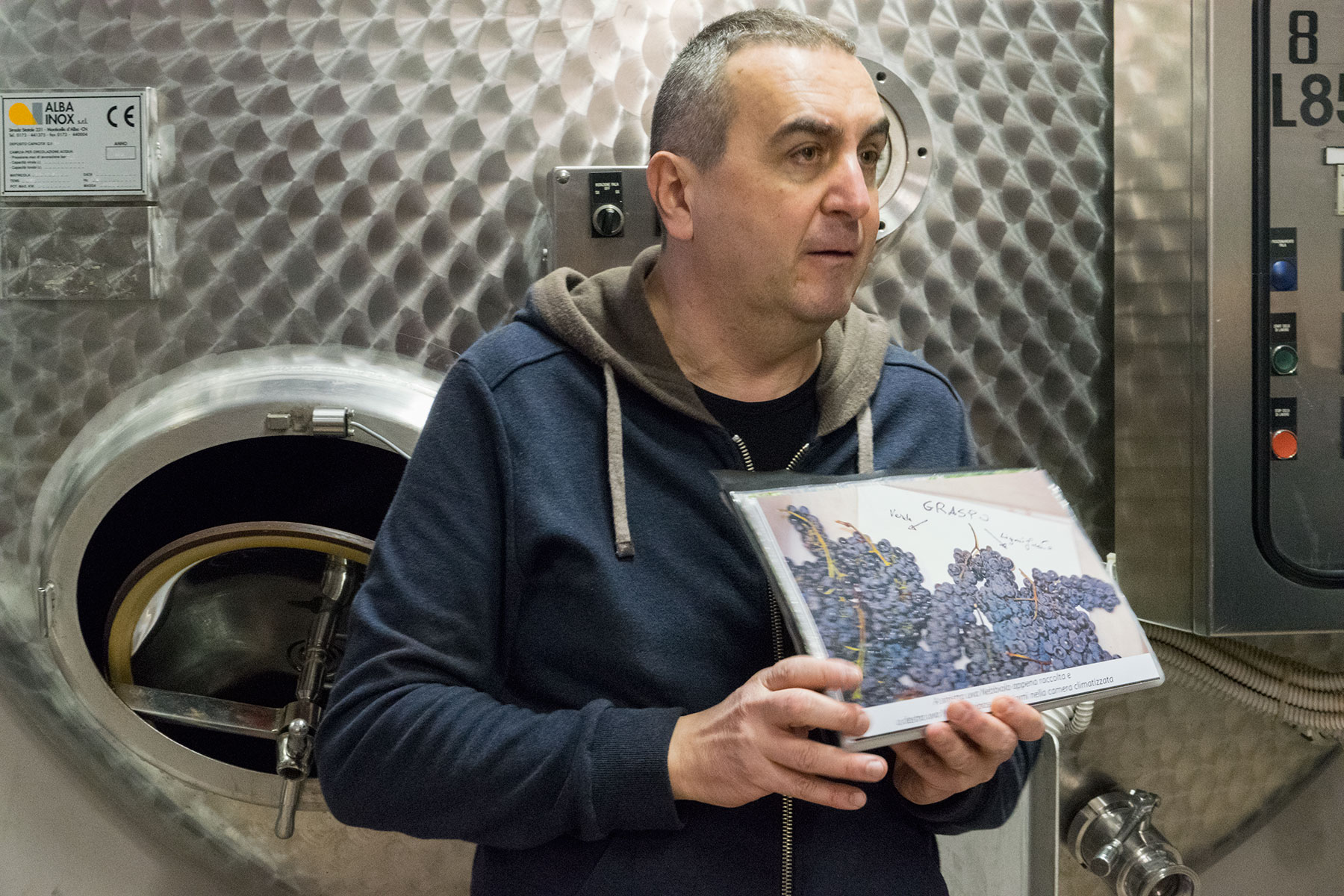

Reliving myself from the brisk wind we would first check out the fermentation room. Stainless steel fermentation tanks are less romantic but Marco is dedicated to his sophisticated equipment. Whole de-stemmed berries (no traditional tumbler de-stemmer) are dumped into vertical tanks with internal blades to keep the skins and juice in contact of each other. “You no longer have to sleep in the cellar.” explains Marco. If temperatures range outside of the desired range or there is an error, an alert is sent to his cell phone. Marco allows the natural yeast to take care of the 10 day fermentation. Marco prefers a shorter fermentation for a more elegant, lighter style. The creamy and rich texture of his wines come in the barrel room with a unique procedure called Autolysing.

The small, outside, above-ground barrel room is full of the best new barrel producers. Inside the barriques is a lees rich environment- a murky wine, that is not clear, and full of grape dust. Over the next year after malolactic conversion the juice inside will be stirred every week, and then once a month towards the end of the year. “

The ground floor of Marco’s home resides the tradition cellar, where his father and grandfather made wine. Traditionally in the 1950s the wine would solely be produced in 20 – 50hl Slovenian oak barrels. Whole bunches would ferment over a long period of time, the stems would eventually fall to the bottom of the vat, removed, and the juice put back into the oak. The wine would be kept here for 4 years, required by law.

Fast forward to Marco’s style of production, after the autolysing process, the wine is brought into the large casks. They significantly slow down the ageing process. Time allows the polyphenols to rest and soften without losing freshness and character. The maturing Brunello will rest in these casks for another year to year and a half at which time the juice is bottled and left to age for another year.

The first wine I would taste with Marco was a tank sample of his 2013 Rosso di Montalcino. The one year in second-hand wood expresses clove and cinnamon spice backed by wild flowers and berries. Bright acidity keeps grippy tannins in check. This Rosso was quite energetic and expressive of the higher yielding but lower alcohol vintage.

A more mature vintage in 2012, Marco’s 2012 IGT Sangiovese showed bright red cherries and raspberries. The youngest vines pure pure fruit and see no oak. Tannins were soft, though the wine lacked structure.

2009 and 2010 couldn’t have been more different. Montalcino experienced a long hot summer in 2009 while up until mid-August in 2010 the temperature was cooler with rains. The end of August was the hottest weekend and the heat continued. This proved for a perfect vintage. A late harvest with good maturity attached with acidity and freshness. It was the making of a grand vintage. Marco’s 2009 Brunello do Montalcino was complexed with earth, barnyard, mushroom, tobacoo and dried red cherry. Tannins were grippy and rustic with balanced acidity, but the fruit character was already dried with not much flavor concentration. On the other hand Marco’s 2010 Brunello was lively with ripe wild berries, raspberry, wild flowers, tobacco, and sweet spice. Tannins were still grippy, but less rustic and more silky. Marco’s autolysing technique showed through more in the 2010 expressing a creamy and silky mouthfeel. Though, the wine was not heavy handed showing great balance and freshness.

In the best years, Marco produces Il Divaso, a single vineyard wine from the oldest plots, respectfully named after his father. 2007 was his most recent vintage, not produced in 2008 and 2009. Il Divaso expressed black currant, tobacco, cedar, and lucious red cherry. Powerful silky tannins, sharp acidity, and highly concentrated. This is a wine for the ages.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.